by Jim Harrison

1.

to D.G.

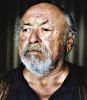

This matted and glossy photo of Yesenin

bought at a Leningrad newsstand—permanently

tilted on my desk: he doesn’t stare at me

he stares at nothing; the difference between

a plane crash and a noose adds up to nothing.

And what can I do with heroes with my brain fixed

on so few of them? Again nothing. Regard his flat

magazine eyes with my half-cocked own, both

of us seeing nothing. In the vodka was nothing

and Isadora was nothing, the pistol waved

in New York was nothing, and that plank bridge

near your village home in Ryazan covered seven feet

of nothing, the clumsy noose that swung the tilted

body was nothing but a noose, a law of gravity

this seeking for the ground, a few feet of nothing

between shoes and the floor a light-year away.

So this is a song of Yesenin’s noose that came

to nothing, but did a good job as we say back home

where there’s nothing but snow. But I stood under

your balcony in St. Petersburg, yes St. Petersburg!

a crazed tourist with so much nothing in my heart

it wanted to implode. And I walked down to the Neva

embankment with a fine sleet falling and there was

finally something, a great river vastly flowing, flat

as your eyes; something to marry to my nothing heart

other than the poems you hurled into nothing those

years before the articulate noose.

2.

to Rose

I don’t have any medals. I feel their lack

of weight on my chest. Years ago I was ambitious.

But now it is clear that nothing will happen.

All those poems that made me soar along a foot

from the ground are not so much forgotten as never

read in the first place. They rolled like moons

of light into a puddle and were drowned. Not even

the puddle can be located now. Yet I am encouraged

by the way you hanged yourself, telling me that such

things don’t matter. You, the fabulous poet of

Mother Russia. But still, even now, schoolgirls

hold your dead heart, your poems, in their laps

on hot August afternoons by the river while they wait

for their boyfriends to get out of work or their

lovers to return from the army, their dead pets to

return to life again. To be called to supper. You

have a new life on their laps and can scent their

lavender scent, the cloud of hair that falls

over you, feel their feet trailing in the river,

or hidden in a purse walk the Neva again. Best of all

you are used badly like a bouquet of flowers to make

them shed their dresses in apartments. See those

steam pipes running along the ceiling. The rope.

3.

I wanted to feel exalted so I picked up

Doctor Zhivago again. But the newspaper was there

with the horrors of the Olympics, those dead and

perpetually martyred sons of David. I want to present

all Israelis with .357 magnums so that they are

never to be martyred again. I wanted to be exalted

so I picked up Doctor Zhivago again but the TV was on

with a movie about the sufferings of convicts in

the early history of Australia. But then the movie

was over and the level of the bourbon bottle was dropping

and I still wanted to be exalted lying there with

the book on my chest. I recalled Moscow but I could

not place dear Yuri, only you Yesenin, seeing the Kremlin

glitter and ripple like Asia. And when drunk you appeared

as some Bakst stage drawing, a slain Tartar. But that is

all ballet. And what a dance you had kicking your legs from

the rope—We all change our minds, Berryman said in Minnesota

halfway down the river. Villon said of the rope that my neck

will feel the weight of my ass. But I wanted to feel exalted

again and read the poems at the end of Doctor Zhivago and

just barely made it. Suicide. Beauty takes my courage

away this cold autumn evening. My year-old daughter’s red

robe hangs from the doorknob shouting Stop.